I yanked back the bolt on the rifle. A spent cartridge spun wildly out of the breech. I rammed the bolt forward. It smoothly picked up another round. I quickly slammed down the bolt and locked the breech just as another wild-eyed soldier clawed to the top of the muddy berm, his long sandy hair snapping like a nest of vipers. Taking a practiced but panicked aim, I flattened the trigger. The exploding gunpowder roared in my ears. A quarter-sized hole punched through the enemy soldier’s forehead and a grisly spray of blood, brains and bone shot out of the back of his skull, the gore coating an army of screaming enemy soldiers who were already clawing over the falling corpse. I held my ground, yanked back the rifle bolt, and the spent cartridge sprung free. I tried to ram the bolt forward to load another round. But the bolt wouldn’t budge. The weapon had jammed. Without thinking, I flipped the rifle around, the smoking hot barrel searing into the flesh of my hands. Feeling no pain, the heft of the rifle butt balancing into an extension of my own fists, and I started swinging. Heads exploded, faces splattered, teeth flew as a berserker’s rage tunneled my vision into a burning red cone, the hue and cry of battle all around reduced to the delicate patter of rain.

While all of this was going on Diane was at the hair salon, enduring a nightmare of an entirely different sort.

Working the floor of a busy salon, Diane was creating elaborate hairdos in a busy shop full of pleasant, every-day patrons. However, each patron was accompanied by a ghostly spirit. These ghosts all looked like every-day citizens, save for their transparent flesh, their malevolent eyes, and their evil tendencies. Were it not for the vigilant supervision of their earthly flesh-and-blood minders, the bad spirits would cause great harm. The salon bustled along normally (albeit creepily) enough, the bad ghosts, like bad dogs, attempting to do harm to the living at every opportunity while their living minders kept a lid on things. Diane turned her back on a patron and leaned against a work station for some scissors. She felt a presence press in. Suddenly, she was shoved against the work station. Cold hands snatched her wrists, pressing hard. The scissors trembled in her hand. Suddenly, she was spun around. An evil spirit was assaulting her. This evil ghost (called “Michael the Bad Ghost”—I’m not making this up), grabbed a fist-full of Diane’s hair. Diane, struggling, scissors clattering to the hard floor, frantically looked for the bad ghost’s living minder. But that person was nowhere to be seen. Unleashed, Michael the Bad Ghost yanked Diane by the hair and drew her closer, closer, closer still, until … until Diane woke herself up.

It was a rough night for the both of us, and we spent the better part of the morning going over our respective dreams. I should also mention that, the day before, we had poked through an afternoon at the Petersburg National Battlefield.

Petersburg National Battlefield is a place of many ghosts—many confused and angry ghosts, it would seem. I’m not one to put much stock in the bad ju-ju of bad sprits, much less bad spirits who cause bad dreams, but I’m otherwise at a loss to explain our common reaction to the Petersburg battlefield. Unlike other places of unimaginable horror (say, the remains of a Nazi concentration camp), the creep-out factor at Petersburg was, for us, curiously absent. Indeed, like any good national park it is a pleasant enough place to visit and even picnic.

For those who don’t know, Petersburg, VA was a pivotal place during the final stages of the American Civil War. More than 70,000 men perished during what would be a grueling 10 month-long siege of the city. Both sides were dug in. The Confederates were desperate to hold the city: If Petersburg fell then their capitol Richmond, VA would fall soon thereafter, and the outcome of the war would be sealed in favor of the Union. This is how the Confederate commander Robert E. Lee saw it. This is how the Union commander Ulysses S. Grant saw it.

And so it was. Lee’s army supply lines essentially held steady during the siege. Meanwhile, Grant’s army shipped in an absolutely huge cache of war material at City Point, a small town just east of Petersburg. Grant would have all he needed to finish things, should his troops break the lines at Petersburg. This is a shot of Grant's HQ cabin, then and now.

Back to the Petersburg battle fortifications, located just east of the city’s downtown. In places, the trench lines were as little as 100 yards apart. Over those hard 10 months, the cannon fire never ceased and the building and rebuilding of the fortifications never stopped. This is a small-scale replica of a typical position. It’s interesting to crawl around on now.

But back then it was a horrible place to be. Life in the fortifications was, as one Union soldier wrote, “Endurance without relief; sleeplessness without exhilaration; inactivity without rest; and constant apprehension requiring ceaseless watching."

(The camera for both of the above images was placed in about the same location.)

Clearly, something had to be done to break the stalemate. Spurred by the offhand suggestion of a former Pennsylvania coal miner, Lt. Col. Henry Pleasants put his regiment of troops to digging. Their objective: to tunnel under the Confederate line, pack that tunnel with explosives, and blow a hole through the enemy line so big that, ultimately, the Rebs would be routed, the stalemate at Petersburg would end, Richmond would fall, and the war would end in the favor of the Union. The Union top brass quickly signed off and work began.

That was the plan. This is what happened.

Starting June 25, 1864, and continuing on for the next month, Lt. Col. Henry Pleasants’ Pennsylvania coal miners quietly burrowed a shaft 511 feet into the hillside under a particularly strong section of the Confederate line. They then packed the tunnel with four tons of powder.

On July 30, at 3:15 a.m., Pleasants lit the fuse and scrambled out of the tunnel.

At 4:40 a.m., two regiments of Confederate soldiers lay sleeping under the sputtering powder keg. In a thunderous quake, the earth below them evaporated and a great crater was ripped from the ground—170 feet long, 80 feet wide, and 30 feet deep. Two hundred seventy eight Confederate troops were instantly blown to hell or heaven or wherever they were destined. Thousands of survivors were hurled into chaos. Some ran in circles. Some remained frozen, paralyzed with fear. Others vaguely scratched at the fortifications as if trying to escape. Smoke and dust filled the air.

Union troops then attacked. However, the troops were unprepared. Weeks prior to the attack, a regiment of black troops had practiced their role as the spearhead for the assault. But late on July 29—hours prior to the big bang—fearing public outcry should the black troops suffer heavy casualties, the Union’s top brass picked another, all-white division to lead the attack. These untrained troops faltered in the smoking maw of The Crater. The Union attack stalled. Confederate forces regrouped. More Union troops were called in—some 15,000 in all. The result was a brutal, confused brawl that decimated both sides, including the formerly-spared black troops. It was a day not of glory and triumph but of indescribable horror.

When all was said and done the Confederates held their line, took possession of The Crater, and later even incorporated it into their defenses. As one Union solider wrote after the fact: “It is agreed that the thing was a perfect success, except it did not succeed.”

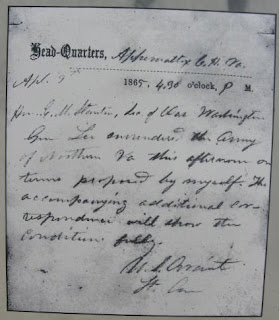

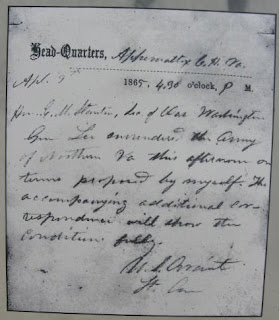

The war continued on, of course. Petersburg eventually fell to Union forces. As predicted, Richmond fell soon thereafter. As predicted, Lee’s Rebs went on the run and Grant and his army gave chase. It was a cat and mouse affair that finally ended when Grant’s troops pinned Lee’s to the ground near the humble town of Appomattox Court House, VA, some 90 miles west of Richmond. The rebellion was finished, save for the paperwork. And so the two generals met as only gentleman do, in the parlor of the fanciest house in town*.

Grant, under orders from Lincoln to be lenient, gave the terms. Lee read them and, with no other choice, accepted them and left.

And the American Civil War was officially over.

But before we break out the fireworks and strike up the band, before important people say important words on important stages, we need to go back to The Crater at Petersburg for a moment. If you could go back to 1867, a scant two years after the official end of the war, this is what you’d see. Notice the skull at the bottom of the image.

And this is what you’ll see today.

But why should we go back at all? The Crater doesn’t look like much of anything now, and this stale old war is long since over.

We go back because The Crater endures, the clover on its grassy knolls as sweet as a summer’s dream. We go back because the ghosts are there, too, demanding our attention. We go back because the attention they demand does not so much require that we listen to the howl of their confused and angry voices, but that we remember their plight, that we acknowledge their torment, that we put our feet upon the very ground of their every step and misstep, lest we too doom ourselves to the hellish realm of endurance without relief; sleeplessness without exhilaration; inactivity without rest; and constant apprehension requiring ceaseless watching.

* The town of Appomattox Court House in general and the McLean House specifically (the actual site of the generals’ meeting) are faithful recreations of the actual place. It looks and feels “real” but it isn’t. The town was abandoned after the war and it wasn’t until the 1930s that the US government took possession of the entire township and began the process of rehabilitating it. Through much hard work and careful planning, the village looks much as it did in April, 1865. All well and good. But this is the interesting part: In 1893 speculators hot on a can’t-miss money-making scheme, bought the McLean House, completely dismantled it, and went about shipping it to Washington DC where they planned to rebuild it and then charge admission to curious tourists. However, the house never made it to DC, the house was never rebuilt, and the parts were scattered to the four winds. The McLean House you see today was built on the old house’s original foundations using the speculators’ own detailed plans and specifications with only several pieces of wood near the fireplace being original. If this isn’t a fitting postscript to an all-American war story, I don’t know what is.

No comments:

Post a Comment